|

This day, Maundy Thursday (also "Holy Thursday" or "Shire

Thursday"1) commemorates Christ's

Last Supper,

the initiation of the Eucharist, the institution of the priesthood, and

our Lord's Agony in the Garden of Gethsemani on the Mount of Olives.

Its name of "Maundy" comes from the

Latin word mandatum, meaning "command." This stems from Christ's words

in John 13:34, "A new commandment I give unto you." It is the first of

the three days known as the "Triduum," and after the Vigil tonight, and

until the Vigil of Easter, a more profoundly somber attitude prevails

(most especially during the hours between Noon and 3:00 PM on Good

Friday). Raucous amusements should be set aside...

The Last Supper took place in "the upper room" of the house believed to

have been owned by John Mark and his mother, Mary (Acts 12:12). This

room, also the site of the Pentecost,

is known as the "Coenaculum" or

the "Cenacle" and is referred to as "Holy and glorious Sion, mother of

all churches" in St. James' Liturgy. At the site of this place -- our

first Christian church -- a basilica was built in the 4th century. It

was destroyed by Muslims and later re-built by the Crusaders.

Underneath the place is the tomb of David.

The Cenacle, or "The Upper Room"

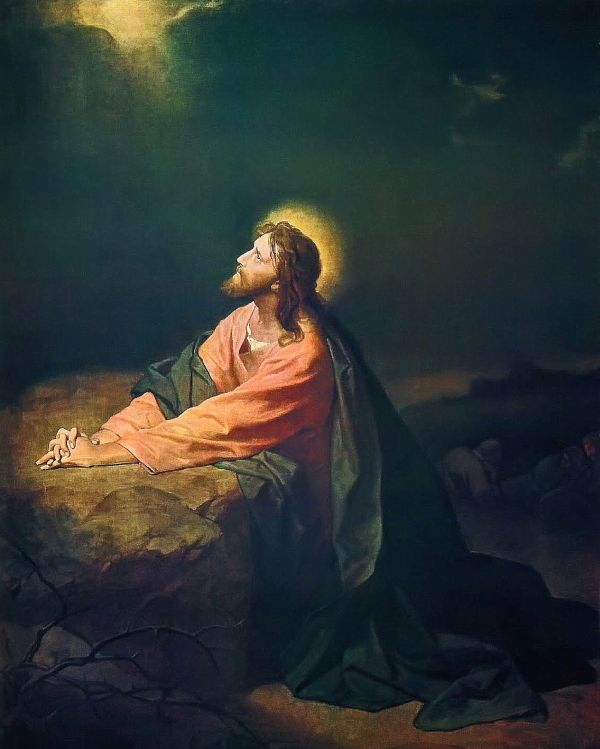

After the Supper, He went outside the Old City of Jerusalem, crossed

the Kidron Valley, and came to the Garden of Gethsemani, a place whose

name means "Olive Press," and where olives still grow today. There He

suffered in three ineffable ways: He knew exactly what would befall Him

physically and mentally -- every stroke, every thorn in the crown He

would wear, every labored breath He would try to take while hanging on

the Cross, the pain in each glance at His mother; He knew that He was

taking on all the sins of the world -- all the sins that had ever been

or ever will be committed; and, finally, He knew that, for some people,

this Sacrifice would not be fruitful because they would reject Him.

Here He was let down by His Apostles when they fell asleep instead of

keeping watch, here is where He was further betrayed by Judas with a

kiss, and where He was siezed by "a great multitude with swords and

clubs, sent from the chief Priests and the ancients of the people" and

taken before Caiphas, the high priest, where he was accused of

blasphemy, beaten, spat upon, and prepared to be taken to Pontius

Pilate tomorrow morning.

As for today's liturgies, in the morning, the local Bishop

will offer a

special Chrism Mass during which blesses the oils used in Baptism,

Confirmation, Holy Orders, Unction, and the consecration of Altars and

churches.

At the evening Mass, after the bells ring during the Gloria, they are

rung no more until the Easter Vigil (a wooden clapper called a

"crotalus" is used insead). French parents explain this to their

children by

saying that the all the bells fly to Rome after the Gloria of the Mass

on Maundy Thursday to visit the Pope. Children are told that the bells

sleep on the roof of St. Peter's Basilica, and, bringing Easter eggs

with them, start their flight home at the Gloria at the Easter Vigil,

when when they peal wildly.

Then comes the Washing of the Feet after the homily, a rite performed

by Christ upon His disciples to prepare them for the priesthood and the

marriage banquet they will offer, and which is rooted in the Old

Testament practice of foot-washing in preparation for the marital

embrace (II Kings 11:8-11, Canticles 5:3) and in the ritual ablutions

performed by the High Priest of the Old Covenant (contrast Leviticus

16:23-24 with John 13:3-5). The priest girds himself with a cloth and

washes the feet of 12 men he's chosen to represent the Apostles for the

ceremony.

As an aside, back when Kings and Queens of England were Catholic, they,

too, would emulate Christ by washing the feet of 12 subjects, seeing

the footwashing rite also as an example of service and humility. They

would also give money to the poor on this day, a practice said to have

begun with St. Augustine of Canterbury in A.D. 597, and performed by

Kings since Edward II. Now the royal footwashing isn't done (it was

given up in the 18th c.), but a special coin called "Maundy Money" is

still minted and given to the selected elderly of a representative town.

The rest of the Mass after the Washing of the Feet has a special form,

unlike all other Masses. After the Mass, the priest takes off his

chasuble, and vests in a white cope. He returns to the Altar, incenses

the Sacred Hosts in the ciborium, and, preceded by the Crucifer and

torchbearers, carries the Ciborium to the "Altar of Repose," also

called the "Holy Sepulchre," where it will remain "entombed" until the

Mass of the Presanctified on Good Friday.

Then there follows the Stripping of the Altars, during which everything

is removed as Antiphons and Psalms are recited. All the glorious

symbols of Christ's Presence are removed to give us the sense of His

entering most fully into His Passion. Christ enters the Garden of

Gethsemani; His arrest is imminent. Fortescue's "Ceremonies of the

Roman Rite Described" tells us: "From now till Saturday no lamps in the

church are lit. No bells are rung. Holy Water should be removed from

all stoups and thrown into the sacrarium. A small quantity is kept for

blessing the fire on Holy Saturday or for a sick

call." The joyful

signs of His Presence won't return until Easter begins with the Easter

Vigil Mass on Saturday evening.

And, of course, tomorrow's Matins and Lauds may be read as part of the

"tenebrae service" (see Spy Wednesday).

Customs

A prayer for the

day:

O Jesus, through

the abundance of Thy love, and in order to overcome our

hardheartedness, Thou pourest out torrents of Thy graces over those who

reflect on Thy most Sacred Sorrow in the Garden of Gethsemane, and who

spread devotion to it. I pray Thee, move my soul and my heart to think

often, at least once a day, of Thy most bitter Agony in the Garden of

Gethsemane, in order to communicate with Thee and to be united with

Thee as closely as possible.

O Blessed Jesus, Thou, who carried the immense burden of our sins that

night, and atoned for them fully; grant me the most perfect gift of

complete repentant love over my numerous sins, for which Thou didst

sweat blood.

O Blessed Jesus, for the sake of Thy most bitter struggle in the Garden

of Gethsemane, grant me final victory over all temptations, expecially

over those to which I am most subjected.

O suffering Jesus, for the sake of Thy inscrutable and indescribable

agonies, during that night of betrayal, and of Thy bitterest anguish of

mind, enlighten me, so that I may recognise and fulfil Thy will; grant

that I may ponder continually on Thy heart-wrenching struggle on how

Thou didst emerge victoriously, in order to fulfil, not Thy will, but

the will of Thy Father.

Be Thou blessed, O Jesus, for all Thy sighs on that holy night; and for

the tears which Thou didst shed for us.

Be Thou blessed, O Jesus, for Thy sweat of blood and the terrible

agony, which Thou dist suffer lovingly in coldest abandonment and in

inscrutable loneliness.

Be Thou blessed, O sweetest Jesus, filled with immeasurable bitterness,

for the prayer which flowed in trembling agony from Thy Heart, so truly

human and divine.

Eternal Father, I offer Thee all the past, present, and future Masses

together with the blood of Christ shed in agony in the Garden of Sorrow

at Gethsemane.

Most Holy Trinity, grant that the knowledge and thereby the love, of

the agony of Jesus on the Mount of Olives will spread throughout the

whole world.

Grant, O Jesus, that all who look lovingly at Thee on the Cross, will

also remember Thy immense Suffering on the Mount of Olives, that they

will follow Thy example, learn to pray devoutly and fight victoriously,

so that, one day, they may be able to glorify Thee eternally in Heaven.

Amen.

As to customs,

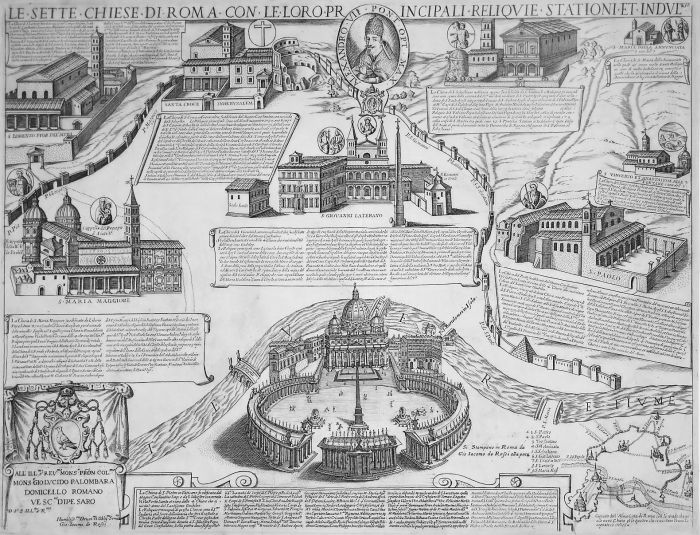

many Catholics have a practice of visiting the tabernacles of seven

churches altogether, starting on this day and on through Holy Saturday,

as a sort of

"mini pilgrimage." In Rome, the list of

the seven churches was chosen

centuries ago and consists of the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano;

Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano; Basilica di San Paolo fuori le

mura; Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore; Basilica di San Lorenzo fuori

le mura; Basilica di Santa Croce in Gerusalemme; and San Sebastiano

fuori le mura. Check here to see

these seven churches on Google maps.

Map of

the Seven Churches. Click to enlarge

Outside of Rome, any seven Catholic churches would do. Some families

visit the churches directly after the evening Mass; others go home and

wake up in the middle of the night to make the visits (though since

churches are rarely open all night these days, this would be hard to

do). The spirit of the visits to the churches is keeping vigil with

Jesus in the

Garden of Gethsemani while He prayed before His arrest.

In Latin countries, Jordan almonds (confetti)

are eaten today and

also throughout Eastertide. In Germany, Maundy Thursday is known as

"Green Thursday"

(Grundonnerstag), and the

traditional foods are green vegetables and

green salad (especially spinach salad), an herb-heavy green soup, or

Frankfurter Green Sauce served

with boiled eggs and potatoes:

Frankfurter Grüne Soße (Frankfurter Green

Sauce)

4 large hard-boiled eggs, peeled

1 cup plain Greek yogurt

2 cups quark (or sour cream)

1 tablespoon lemon juice

2 tablespoons olive oil

2 green onions, finely chopped

1/2 teaspoon sugar

salt and freshly ground pepper (white pepper, if possible), to taste

3 cups finely chopped mixed herbs: borage, chervil, cress,

parsley, salad burnet, sorrel, and chives*

Halve the eggs and mash the yolks up with everything else but the egg

whites (you can put everything in a blender, if you like. Some add a

tablespoon of hot German mustard as well). Let it sit in the fridge for

an hour or so, then chop the egg whites and sprinkle on top. Serve over

halved boiled eggs, boiled new potatoes (the small, waxy kind), and/or

flaky white fish.

* If you have trouble finding some of the herbs, you can replace some

of them with some combination of cilantro, tarragon, summer

savory, lovage, lemon balm, spinach leaves, or arugula. It won't be the

same, but will be delicious.

In Czechoslovakia, the food of the day is Jidáše, or "Judas

Buns" -- little buns made of sweet pastry that are said to resemble

spirals of the rope Judas used to hang himself with. The eating of

honey on Maundy Thursday is considered good luck in Czechoslovakia, and

these buns make use of that lore:

Jidáše (Judas Buns)

4 cups all-purpose flour

1 1/4 cups whole milk, slightly warmed - divided

2 teaspoons active dry yeast

2/3 stick unsalted butter

2 egg yolks, at room temperature

1 tsp lemon zest

1/3 cup granulated sugar - divided

pinch of salt

1 whole egg

1 tablespoon honey, warmed

Put the flour into a bowl and make a well. Pour into the well

2/3 c. of the lukewarm milk. Add 1/2 teaspoon of sugar. Add the yeast.

Stir the flour in from the sides until a thick, doughy batter forms.

Dust lightly with flour and let it rise for 30 minutes.

Meanwhile, melt the stick of butter and let it cool to just warm. When

the 30 minutes are up, add the butter to the dough along with the egg

yolks, lemon zest, salt, remaining milk, and sugar. Stir everything up

and then knead for about 10 minutes on a floured surface. Then let the

dough rise for another 30 minutes.

Divide the dough into 10 pieces. Roll each piece into a rope that's

about 10 inches long, then form each rope into a spiral, tucking the

end up and underneath the spiral. Place onto a parchment-lined sheet,

cover them with a moist tea towel, and let them rise for another 45

minutes.

Heat oven to 350F. While the oven's heating, beat up the whole egg and

baste the tops of the pastries with it. When the oven's ready, bake the

buns for about 15-25 minutes until golden. Glaze the tops of the buns

with the warmed honey while they're still hot.

On this day, one may gain a

plenary

indulgence, under the usual

conditions, by reciting the Tantum Ergo

(Down in Adoration Falling).

Note, too, that this is a good day to especially remember priests and

express gratitude toward them.

Relevant Scripture for Maundy Thursday: Matthew 26:17-56; Mark

14:12-52; Luke 22:7-54; John 12:20-50, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18:1-13.

For further spiritual reading, you might benefit from The Agony of Our Lord in

the Garden (pdf) by Padre Pio, from

this site's Catholic

Library.

Reading

From The Life of Christ, Volume III

by E. Le Camus,

Bishop of La Rochelle and Saintes, France

It must have been about ten o’clock in the evening. Through the already

deserted streets of the city Jesus and the Apostles descended into the

valley of Cedron towards the Mount of Olives. This was the road to

Bethany; but on that evening Jesus was not to return to His friends’

house.

Crossing the bed of the river the Apostolic group halted before a

garden called Gethsemane or the Oil-press.” The grove, which was

probably enclosed, contained a kind of pleasure resort." It may be that

the proprietor was a friend of Jesus. Many have thought that Gethsemane

belonged to the family of Lazarus. In any case, it was not the first

time that the Master came there, and no doubt it was the custom to

assemble there as at a meeting place on leaving Jerusalem and before

setting out for the village of Martha and Mary. Although He foresaw

that Judas would bring His enemies to this spot, He was not led to

modify this usual evening programme.

Jesus entered the enclosure, and, inviting the Apostles to sit down and

await Him near the entrance, perhaps in the dwelling-house, He advanced

into the middle of the grove, with Peter, James and John, to pray. The

great drama was beginning. Perceiving the approach of the fatal hour,

the Redeemer sought to meet His Father face to face to hold converse

with Him. The great voice of God which long ago in the shades of Eden

had summoned fallen man: “Adam, Adam, where art thou?” had been for

four thousand years without ananswer. No son of sinful humanity had had

the courage to respond: “Here am I!” It was for the New Man to break

that silence. For Jesus, indeed, ready to pay for all, seems to advance

towards the divine wrath, exclaim ing: Ecce Venio ! Adam awaits his

judge!

By this free and generous act He meant to assume humanity entire

together with the responsibility for its crimes, and to speak, to act,

to expiate as if He alone were mankind. Thus He constituted Himself

really a New Man summing up by substitution in His life the lives of

all, in His heart the hearts of all, and in His soul the souls of all.

But what crushing responsibilities such an acceptance involved! By

saying to His Father: “Forget Thy Son now, and behold in Me only fallen

humanity asking that it may expiate its long-continued faithlessness;

let Thy justice have full play!” He gave Himself up to every torture,

for the crimes of humanity are most varied and countless. If each one

of these required a special reparation, how terrible was the blow which

all of them together could inflict upon the body, the heart, and the

soul of Him Who presented Himself as an atonement for them all! The

more so, since, however hard the labour, Jesus, in order to furnish it,

could look for help from no one. He alone, according to the prophet’s

words, was to enter the press of the divine wrath.

There was an added circumstance in His sufferings that made His agony a

trial as intolerable for Him as it is mysterious to us. Suddenly, into

His soul which, of its own right and from the moment of His birth, had

enjoyed the beatific vision, there came a strange eclipse. God seemed

to withdraw Himself, He seemed to abandon the Man to His own resources

with a rigour that knew no pity; He concealed Himself so completely as

to provoke that heart-rending cry which was afterwards heard from the

Cross: “My God, why hast thou forsaken me?” How may we understand this

prodigious phenomenon, since the hypostatic union is indissoluble? Our

eye cannot penetrate the cloud; our curiosity must halt before problems

of so transcendent an order. It is a mystery. Whatever one may say, one

cannot explain it, one can only run the risk of compromising its

harmony. Let us be firmly content with these two data of the problem,

both of which are equally incontestable: the divine nature in Jesus was

inseparable from the human nature, and yet the latter underwent the

trial, struggled and suffered as if it had been separated from the

former. For we cannot imagine a more bitter and more real agony than

that which causes a sweating of blood.

The picture traced for us by the Synoptics of Jesus’ condition at the

moment when He leaves His disciples is striking. The humanity of our

Lord is there fully seen in all its reality and its holiness. A vague

terror weighs Him down and crushes Him. A loathing soon follows, and

moves Him to profound sadness. This trembling of the whole being

belongs to the essential phenomena of life. The purer and the more

guarded humanity is from the violent passions, the more delicate and

sensible it is beneath the embrace of moral woe. No longer checking His

emotion, the Master began to speak: “My soul is sorrow ful even unto

death!” It was a quick transition from that sweet peace, which had

inspired in Him the last farewell at the Supper, to a sudden agitation

that disturbs His whole moral being. But does not the stone suddenly

loosed from the mountainside spoil the clearness of the spring by

stirring it to its depths? Does not the hurricane on a sudden hurl up

the waves of the ocean and the sands of the desert? To hide the sight

of His agony from the three privileged disciples, the Master withdraws

a few steps away. It seems that although he derived a human consolation

from their presence, He preferred to stand apart from them through fear

of doing them harm.

“Stay ye here,” He said to them, “and watch with Me. Pray lest ye enter

into temptation.” His thought was then, to associate them, though at a

distance, in the great act of love, of obedience, of sacrifice which He

was about to accomplish. Alas! He was to find in them, who were the

elect of the Apostolic college, only drowsy men with out any true sense

of the solemnity of this occasion. He withdrew perhaps a stone's throw,

says the Evangelist, and fell on His knees. This attitude befitted the

Victim awaiting the mortal blow, and testing it in advance, as if to

know its full violence. Even if He had not with His prophetic glance

sounded the abyss of woes into which He was about to descend, Satan

would have taken care to place before His eyes this dark repulsive

picture. We know that the tempter, after his first vain struggle, had

held himself in reserve awaiting a favourable" opportunity later on for

a fresh attack. The present hour was once more his,” and Jesus desired

in vain to escape it.”

As he had been in the desert, Satan was also in Gethsemane. Temptation

is directed against man’s heart sometimes by violent desires, sometimes

by foolish fears. Jesus had long ago been insensible to covetousness,

would He allow Himself now to be overcome by fear? Satan, in the midst

of light mingled with darkness, might have asked himself this. When he

is desirous of capturing man through fear, his cleverness consists in

injecting a vague terror into the soul, repugnance into the heart,

hesitation into the will. Thus he often overturns our resolutions, our

aspirations and our strongest convictions.

To Jesus, Who had come into the presence of His Father to confer

concerning our redemption, he represented first of all in the liveliest

colours all the physical and moral sufferings that His enemies held in

store for Him. From Judas’ kiss to the gall mixed with myrrh and

vinegar, from the scene of derision to the final desolation on the

Cross, not forgetting the bloody rods of the flag ellation and the

crown of thorns, from the insulting pride of Caiphas, the cynical

contempt of Herod, the selfish cowardice of Pilate to the insults that

re-echoed on the rock of Calvary, nothing was omitted. Jesus knew

better than he how frightfully severe it all was, and as He beheld the

hideous picture, His first movement of fright was changed into a

sentiment of stupefaction that rendered Him motionless. Immediately, to

make the assault more formidable, Satan seemed to hurl down upon His

soul, one by one, all the crimes of mankind, and to strive to crush Him

beneath the weight of so much infamy. The Just One looked upon His

hands and saw them reeking with the blood shed by the homicides of all

ages. In His astonished soul thundered, as it were, the voices of

impiety and of blasphemy, the abominable outcries of humanity so long

in rebellion, and now suddenly taking refuge in Him to make Him

responsible for its scandalous excesses. His pure heart shook with the

tumult of the most violent passions. The most profound sanctuary of His

soul belonged to God, no doubt, more than ever; but a thick atmosphere

of evil surrounded Him, was overwhelming Him. With quick energy His

unalterable sanctity shook off the horrible cloak of crimes which human

malice was throwing about His shoulders; Satan replaced it on Him with

the words: “If thou wilt wash them away, thou must bear them.” Thus in

famously transformed, the Son would merit naught but the just severity

of His Father. The Well-Beloved became the Accursed. What heroism in

assuming such a responsibility, in accepting the punishment though

guilt less of the fault!

Under the crushing burden which He now received, Jesus had

unconsciously bent His head to earth. The angry countenance of the

Father upon which He has just looked has overwhelmed His soul. He can

bear it no longer, and, rising up: “Father,” He cries out, “if it be

possible, and all things are possible" to Thee, let this chalice pass

from Me! But not what I will, but what Thou wilt.” Satan then has

nothing to do here. It is with His Father alone that Jesus will

conclude the awful contract. Cannot the justice of God remove in some

measure the frightful bitterness of this overflowing chalice? Is sin

then so great an injury that it must be expiated by so terrible a

reparation? Death He has long since accepted, and nothing can prevent

Him from saving the world; but death together with the malediction of

His Father, how can He endure both? And yet He must, because, Lamb of

God though He is, never having known sin, He assumes the place of

sinners. It is because He has taken this place that His suppliant cry

has not penetrated the skies, and the name of the Father uttered with

so much love has remained powerless on His lips.

In reality, He prays with earnestness, but He does not desire to force

the Father’s will which, in this instance, is not in accord with His,

without there being, however, in this divergency even the shadow of an

imperfection. The Father desires the sacrifice; from the viewpoint of

His justice, this is His right. The Son does not desire it, giving ear

to the claims of His human nature, and this is His right. Human nature

was not created for suffering and it instinctively and energetically

rejects it. Without this innate repugnance, the accept ance of grief

would never be a sacrifice. Face to face with the immolation suggested,

nature inevitably and spontaneously cries out: No! This may be called

the will, but it is not the whole will, nor even a part of the true

will, for this instinctive movement is subject to a superior command of

the soul which perceives its duty where the exigencies of a higher

order point it out. This superior command silences the otherwise

legitimate cry of nature, and this it is that adds to the first part of

Jesus’ supplication: “If it be possible, let this chalice pass from

Me!” the second part which reduces it to its true proportions by

removing every possibility of a conflict: “But not what I will, but

what Thou wilt!”

It has been said that the Saviour then suffered all the pains of hell

save despair. It is certain that the emotion of His soul disturbed His

whole physical being. His blood in lively ferment finally broke through

its conducting vessels, and escaped with the abundant perspiration that

was streaming from His whole body. The combat became more and more

violent. His flesh, His soul, His mind, all sought to fly the awful

sacrifice; His will alone stood fast, and holding, so to speak, the

three victims beneath the hand, it dragged them on in spite of

themselves to the immolation, in conformity with that which the

Father’s good pleasure exacted. In Jesus’ life there was nothing

greater than the superhuman struggle so justly called His agony.

As if to fortify Himself by the sight of those He loves, and from whom

He expects perhaps an affectionate word in the midst of this fearful

combination of hate and fury that surrounds Him, the Master rises and

goes to the three disciples whom He had invited to watch and pray with

Him. They had fallen asleep. In a tenderly reproachful tone He turned

to the most devoted among them, to Peter, who promised to go with Him

even to death, were it necessary, and who is not even able to watch

with Him: “Simon, sleepest thou?” He says. “Couldst thou not watch one

hour with me?” He perceives, as if with painful astonishment, but it

is, alas! true, that every one is forsaking Him, even His most

cherished friends for whom He had lived and for whom He was going to

die. Their indifference at so solemn a moment foreboded their

approaching desertion. “Watch ye and pray,” He added, “that ye enter

not into temptation.” Sleep is dangerous when one must decide with

energy. The sleeper no longer sees his duty clearly and he loses

somewhat of the liberty necessary for its fulfilment. In the

solemnevents of life the senses must be on the alert and the soul in

prayer. “The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak. These

words spoke of the terrible trial which He Himself was undergoing. Had

their eyes, less heavy with sleep, beheld the Master's august face in

the pale light of the moon, they would have discovered it to be cruelly

transfigured, not with glory now, as on the mountain, but with grief.

Where formerly a radiant light had shone, there now shone a sweat of

blood. He had reason to say that the flesh is weak, and that a strong

will is necessary to lead it on to death.

Unaided by the Apostles, whom He leaves a second time, Jesus turns once

more to God. Again He prostrates Him self to pour forth lovingly before

Him His desolate soul and His most ardent prayers. His tears and His

blood bathed and sanctified the earth that had remained cursed for

forty centuries. What admirable symbolism! It was in a garden that the

first man had ruined his posterity, it is in a garden that the New Man

prays and suffers that He may save the new humanity; and this garden is

planted with olive-trees, as if this latest sign of peace were

necessary to give true meaning to the treaty that is being concluded

between heaven and earth. Adam had lost us by lifting up His head in

pride, in covetousness, in sensuality, towards the forbidden tree;

Jesus saves us with His face upon the ground in humiliation, in

suffering, in renouncement, under the pacific olive-tree of Gethsemane.

However urgent the august Suppliant may be in His woe, no one seems to

hear Him. He therefore sends forth another cry to heaven, but in it He

gives greater emphasis to His resignation. The Father’s severity, in

fact, seems to make Him more timid. “My Father,” He says, “if this

chalice may not pass away, but I must drink it, Thy will be done!”* It

may not; hence heaven is still silent above Him. Satan at this moment

perhaps explains to Him the uselessness of His sacrifice. The men for

whom He is going to die will mock His sufferings even at the foot of

His Cross. Few only will come to sit and to pray beneath the Tree of

Life. Is it, in truth, worth the trouble to plant it with so much woe

and to bedew it thus with His blood? And Jesus replies: “I will die

nevertheless, and My Father shall be glorified, and My friends shall be

saved.”

He arises to go once more to find the three disciples, the cherished

nucleus of the future Church. To look upon them even sleeping will be a

solace to Him. The silence of the night, in which He hears only the

violent throbbing of His own heart is intolerable. Peter, James, and

John were sleeping more soundly than before. One never sleeps better

than after a deep moral agitation. The emotions of that evening,

sadness, the advanced hour of the night, could not but add to the

heaviness of their eyelids. When the Master spoke, they knew not what

to answer. Jesus, distressed at such a sight, did not insist.

For the last time He withdrew to pray. It may be that this threefold

prayer really corresponded with the sentiments of fear, of loathing,

and of sorrow which, as a threefold temptation, had invaded His heart.

Inexorable and silent, as before, the Father held Himself invisible to

the anxious eyes of the wretched Victim. However, as He seemed almost

undone, He sent an angel to strengthen Him. Like Him the great ones of

earth, that they may the better refuse a favour, withdraw themselves

from the importunities of suppliants, and send their servants with

useless encouragement to those whom they are deputed to dismiss.”

The angel declared that Jesus had conquered. For the struggle was over.

Nature’s last repugnance had just yielded before the justice of heaven

which was inexorable. The human will had been completely broken by the

will of God. Jesus arose resolutely and, rejoining His disciples, still

covered with traces of His bloody strife like an athlete returning

victorious from the combat, He appeared once more possessed of His

usual serenity and strength of soul: “Sleep now,” He said to them, “and

take your rest. It is enough.”

His transition from despondency to courage is as speedy as was that

from tranquillity to anguish. He has seen or heard the enemy

approaching, and He resumes His wonted manner, not without some trace

of trouble or emotion in the rapidity with which His soul and His words

leap as it were from one warning or invitation to another; but it is

evident that His will leads on the Victim in triumph and that mankind

shall be redeemed. “The hour is come,” He exclaims, “Behold the Son of

man shall be betrayed into the hands of sinners. Rise up, let us go.

Behold, he that will betray Me is at hand.”

At the same time, He turned towards the rest of the Apostles who were

at the entrance of the garden. He was eager to protect them against the

enemy who approached. It was about midnight.

Footnotes:

1 The name "Shire

Thursday" is explained in "Festival" printed by Wynkyn de Worde in

1511: "Yf a man aske why Shere Thursday is called so, ye may saye that

in Holy Churche it is called (Cena Domini) our Lordes Souper daye; for

that day he souped with this Discyples openly; and after souper he gave

them his flesshe and his blode to ete and drynke. It is also in

Englysshe called Sher Thursdaye, for in olde faders dayes the people

wold that daye sher there heedes, and clyppe theyr berdes, and poll

theyr heedes, and so make them honest ayenst Ester Day."

|