|

To put it as

simply as possible, Justice is the virtue of giving to others and to

ourselves what is

rightly owed. While Prudence moderates the intellect, Fortitude

moderates the irascible passions, and Temperance moderates the

concupiscible passions, Justice moderates the will.

Aquinas distinguishes two types of justice: commutative justice and

distributive justice. The former pertains to dealings between

individuals, who are treated equally in determining matters of

restitution; the latter pertains to dealings between individuals and

the state -- actors who are treated proportionally and without

favoritism

or prejudice. But since we're undoubtedly all clear on the ideas that

if you take something from someone, you need to pay it back

(restitution), that murder and stealing are wrong, etc., this page will

focus on the potential parts of Justice and the virtues related to it,

specifically: religion, piety, observance, and epieikeia. It is these

virtues that are not

only not clearly understood, but which are under attack -- some to the

point that they no longer exist in the world at large.

Religion

Religion is the virtue of giving God what we owe Him. Of course, our

debt to Him is too large for us to ever pay, but we worship Him as best

we can. This worship -- latria

-- is both of the mind (intellectual assent to the Church's teachings,

mental adoration, prayer, etc.) and the body (e.g., we kneel when we

pray), and sometimes involves a particular place (e.g., we go to church

to adore Him).

I assume that the people reading this have already gotten past the

modern world's New Agey notions against organized religion -- ideas

that ignore Truth and belittle the importance of acknowledging the

body-soul unity, the importance of society, the good of tradition, etc.

And I imagine that you are already aware that you need to be catechized, receive the

sacraments as necessary, embrace the

Church's four creeds, obey the six

precepts of the Church, and have a prayer life. So I will warn

about deficiencies of the

virtue of religion.

Aquinas lists the following as deficiencies: idolatry, divination,

superstition, undue worship, and irreligion (perjury,

sacrilege, simony, and tempting God -- that is, putting

God and His attributes to some sort of test, whether by word or deed,

as Satan did to Christ, and as do those who say things like "If God

existed, He would _____" or "If God is good, He'd ________"). But it is

the problem of undue worship that I want to focus on here, as it's the

problem most pertinent to Catholics in these days.

First, if you haven't read the "Traditional

Catholicism 101" page, I encourage you to do so to get caught up on

the great problem of undue worship (and wrong belief) infecting the the

Church Militant in our times. It goes without saying that we have to

learn the Faith, practice it as it's always been practiced, and pass it

down to our children. Failure to do so is one danger of undue worship.

Another is -- well, I'll quote Aquinas directly. He writes, my

emphasis,

A thing is said

to be in excess in two ways. First, with regard to absolute quantity,

and in this way there cannot be excess in the worship of God, because

whatever man does is less than he owes God. Secondly, a thing is in

excess with regard to quantity of proportion, through not being

proportionate to its end. Now the end of divine worship is that man may

give glory to God, and submit to Him in mind and body. Consequently,

whatever a man may do conducing to God's glory, and subjecting his mind

to God, and his body, too, by a moderate curbing of the concupiscences,

is not excessive in the divine worship, provided it be in accordance

with the commandments of God and of the Church, and in keeping with the

customs of those among whom he lives.

On the other hand if that

which is done be, in itself, not

conducive to God's glory, nor raise

man's mind to God, nor curb inordinate concupiscence, or again

if it be not in accordance with the commandments of God and of the

Church, or if it be contrary to the general custom—which, according to

Augustine [Ad Casulan. Ep. xxxvi], "has the force of law"—all this must be reckoned excessive and

superstitious, because consisting, as it does, of mere externals, it

has no connection with the internal worship of God. Hence

Augustine (De Vera Relig. iii) quotes the words of Luke 17:21, "The

kingdom of God is within you," against the "superstitious," those, to

wit, who pay more attention to externals.

You can pray from the Breviary six times a day, pray a full Rosary and

attend Mass daily, pray constant Novenas for this cause or that -- but

if you don't have charity, you have nothing. I Corinthians 13:1-2

spells this out as plainly as it could be put: "If I speak with the

tongues of men, and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as

sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And if I should have prophecy and

should know all mysteries, and all knowledge, and if I should have all

faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am

nothing." If you have a prayer routine that doesn't lead you to God, if

you are disciplining yourself in ways that make you angry, bitter, or

proud instead of more virtuous and loving, something is wrong, and

something must change. Talk to your priest.

Pages from this site that I hope Catholics read and think about while

keeping in mind the concept of undue worship:

Make a habit of making a Nightly

Examination of Conscience, Or if you're too tired at night, do it

in the mornings. Or at lunch. Or on your drive home from work. But do

it. And do

it well.

Piety

Piety is almost gone in the West, actively drummed out of us by

educators and the media. There's a snarky cynicism about family life

and feelings of patriotism, which are snidely mocked by those who

consider themselves superior to those with senses of loyalty and duty.

The "superior" ones like to think of themselves as "global citizens,"

owing allegiance to no one.

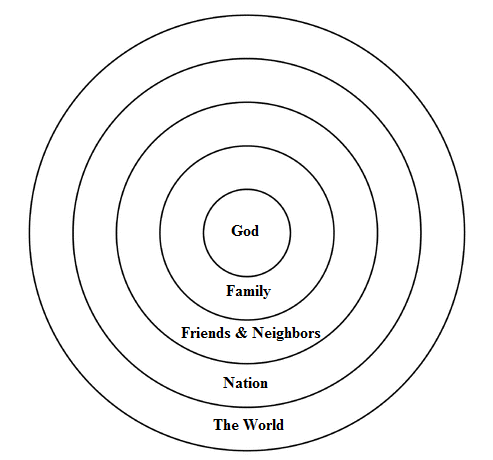

But piety calls us to know and act on the opposite idea: that we owe

more to our families, friends, and nations than we do to strangers and

those of other nations. Our loyalties start with God, then go to

family, then to friends and neighbors, then to nation, and only then to

"the world." Think of these loyalties -- this ordo amoris, or order of charity --

as concentric circles, with God

at the center:

Aquinas writes, on the virtue of piety,

Man becomes a

debtor to other men in various ways, according to their various

excellence and the various benefits received from them. On both counts

God holds first place, for He is supremely excellent, and is for us the

first principle of being and government. On the second place, the

principles of our being and government are our parents and our country,

that have given us birth and nourishment. Consequently man is debtor

chiefly to his parents and his country, after God. Wherefore just as it

belongs to religion to give worship to God, so does it belong to piety,

in the second place, to give worship to one's parents and one's country.

The worship due to our parents includes the worship given to

all our kindred, since our kinsfolk are those who descend from the same

parents, according to the Philosopher (Ethic. viii, 12). The worship

given to our country includes homage to all our fellow-citizens and to

all the friends of our country. Therefore piety extends chiefly to

these.

So many people today busy themselves with trying to "fix the world"

while hating their own people and nations, and most of what they do

causes more trouble than it cures. The busy-bodies tend to be people

who are unable to get their families and personal lives under control,

but feel entitled to "change the world" nonetheless. It's the height of

hubris. But they need to get their own lives in order -- and do so long

before thinking they have what it takes to

take on fixing the world.

If your house isn't in order, you have work to do. Finish it before

trying to order things outside of it. Work to have a healthy family life. Make your

home orderly, peaceful, and beautiful. Do things with each other. Talk

and really listen to each other. Apologize to and forgive each other.

Make great occasions of birthdays, name days,

and feast days. Know your family's history,

and write it down for those

who come after you. Make a family tree (pdfs to help you: 6 generation family tree; 7 generation family tree; 8 generation family tree). Talk

to your children about

their ancestors. Take care of your aging

parents and grandparents; talk

to them, check in on them, tend to their needs, and do so routinely.1

Remember the sad tale of "The Old Grandfather and His Grandson":

Once upon a time

there was a very, very old man. His eyes had grown dim, his ears deaf,

and his knees shook. When he sat at the table, he could scarcely hold a

spoon. He spilled soup on the tablecloth, and, beside that,

some of his soup would run back out of his mouth.

His son and his son's wife were disgusted with this, so

finally they made the old grandfather sit in the

corner behind the stove, where they gave him his food in an

earthenware bowl, and not enough at that.

He sat there looking sadly at the table, and his eyes grew

moist. One day his shaking hands could not hold the bowl,

and it fell to the ground and broke. The young woman scolded, but he

said not a word. He only sobbed.

Then for a few hellers they bought him a wooden bowl and made him eat

from it.

Once when they were all sitting there, the little grandson of

four years pushed some pieces of wood

together on the floor.

"What are you making?" asked his father.

"Oh, I'm making a little trough for you and mother to eat

from when I'm big."

The man and the woman looked at one another and then began to

cry. They immediately brought the

old grandfather to the table, and always let him eat there

from then on. And if he spilled a little, they did not say a thing.

You teach your children and grandchildren how to treat you by how you

treat your parents and grandparents now. Teach your children well.

Then, when your family's made right, look to what you owe your nation.

Loving one's nation and people

doesn't have to entail loving its form of government, or thinking that

anything its leaders decide is good; it means putting its good and the

good of its people before the good of other nations and other people.

It doesn't mean putting other peoples and other nations down, or

thinking your country is better than theirs; it means buoying yours up,

knowing that it is the best for you because

it is your home. Salute your

nation's flag, revere its symbols, obey its just laws, and do what you

can to ensure those laws reflect Christian

social teaching. Know your

country's

form of government and how its laws are made. Work to ensure the

welfare of your people, and teach your children to do so as well.

Observance: Respect

and Affability

Observance concerns the respect owed to those not covered by the

virtues of religion and piety.

Aquinas first describes the respect due to those in positions of

dignity, such as judges, military leaders, kings and queens, governors,

teachers, priests, etc. The practice of kissing a priest's hands or a

Pope's ring, the respect given to a judge in a court of law, referring

to policeman as "sir" instead of "pig," calling teachers by their

titles and last names and showing them respect in their classrooms --

these practices are dying out. And it is sad.

Democracy leads to this sort of "leveling out" of distinctions between

people of different status. As Plato wrote, and as I quoted on the

introduction to this sub-section, in democracies,

the father grows

accustomed to descend to the level of his sons and to fear them, and

the son is on a level with his father, he having no respect or

reverence for either of his parents; and this is his freedom, and the

metic is equal with the citizen and the citizen with the metic, and the

stranger is quite as good as either...

... [T]he master fears and flatters his scholars, and the

scholars despise their masters and tutors; young and old are all alike;

and the young man is on a level with the old, and is ready to compete

with him in word or deed; and old men condescend to the young and are

full of pleasantry and gaiety; they are loth to be thought morose and

authoritative, and therefore they adopt the manners of the young.

He later says,

[S]ee how

sensitive the citizens become; they chafe impatiently at the least

touch of authority and at length, as you know, they cease to care even

for the laws, written or unwritten; they will have no one over them...

Such, my friend, I said, is the fair and glorious beginning out of

which springs tyranny.

And this is where we are. In a world of sassy kids, disrespectful

students, and scofflaws who burn down police stations.

It's so that those in positions of special respect today too often

don't live up to the dignity of the positions they hold -- perhaps to

the point that the positions they hold can be seen to be generally

corrupt. But those positions

should still be respected nonetheless. Remind yourself of this when you

encounter yet another awful teacher, ideologue professor, or dirty

politician.

Aquinas then goes on to speak of the respect owed to people in general,

which he characterizes with the word "affability" or "friendliness." He

writes,

[I]t behooves

man to be maintained in a becoming order towards other men as regards

their mutual relations with one another, in point of both deeds and

words, so that they behave towards one another in a becoming manner.

Hence the need of a special virtue that maintains the becomingness of

this order: and this virtue is called friendliness.

Now, some people are extraverted, and some are introverted, and that's

all well and good. But good manners and a hospitable attitude are for

everyone. What's considered good etitquette changes throughout time,

and fun can be had looking at old books on the subject. From them one

can learn things like "a married lady who dances only a few quadrilles

may wear a decoletée silk dress with propriety" or that "In England, a

lady may accept the arm of a gentleman with whom she is walking, even

though he be only an acquaintance. This is not the case either in

America or on the Continent. There a lady can take the arm of no

gentleman who is not either her husband, lover, or near relative." 2

We may laugh at the specificity and seeming randomness of some aspects

of old-school etiquette, but we can't deny that something good and

crucial has

been lost along with the very convoluted folderol. That etiquette

changes doesn't make the concept ridiculous or not worth thinking

about. Etiquette, whatever it is in one's time and place, makes social

interactions go smoothly. It signals to those present "I respect you."

And that is sorely needed today.

Below are some very basics that I include in "Nonna's

Book of Virtues," written for children, and tweaked here in a place

or two for adults:

In General:

♦ Look around you and see who might need or want something.

Then help them get what they want or need. Is someone carrying

something heavy? Help him! Does someone look hot? Turn a fan on for

him! Does someone look thirsty? Get him a drink. Is Grandma having a

hard time getting out of the chair? Help her up! Use your eyes! And pay

special attention to the elderly, the pregnant, people carrying babies,

the sick, the blind, etc.

♦ If you’re in a place that doesn’t have enough seating, give

up your seat to someone in more need to rest -- the elderly,

pregnant, or sick, etc. Boys are especially to give up their seats for

girls and women. Why? Because boys are stronger!

♦ If someone does something embarrasing, help him to “save

face” – to feel less embarrassed. If no one but you saw or heard him do

the embarrassing thing, you can pretend you didn’t even see or hear it.

If it’s clear to both of you that you did see or hear it, and something

embarrassing has ever happened to you, you can say something like, “Oh,

something like that happened to me once – it was kind of funny.” Smile,

then very quickly change the subject and act as if nothing’s happened.

♦ When dealing with others, pay attention to their moods. If

someone is sad, cheer him up. If he just wants to talk, listen. If he’s

really happy, don’t rain on his parade by talking about sad things.

♦ Don’t gossip. And follow the “Thumper rule”: If you

can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all. (What's meant by

that is "don't speak hurtful truths that are unnecessary or imprudent

to speak." It doesn't mean "niceness" is a greater value than truth. At

all.)

♦ If someone is being unjustly bullied, stand up for him.

Don’t ever

approve of unjust bullying, and don’t engage in it yourself. Ever.

♦ Be on time.

♦ Keep your word.

♦ Apologize when

necessary.

♦ Know how to say

"I don't know" and "I was wrong" when needed.

♦ Don’t ever litter. And that includes cigarette butts: put

spent cigarettes in your cigarette pack if no ashtray is available.

♦ Refer to grown men as “Sir” and grown women as “Ma’am”

or "Madam" unless you’re given permission to call them something else.

If you know

the person’s last name, you can also call him “Mr. Trumblethwaite” – or

call her “Miss Throttlebottom,” or “Mrs. Glickyschtall.” You use

“Miss” for women who are single, and “Mrs.” for women who are married.

If you’re not sure, use “Miss.” (Sadly, some women prefer to be called

“Ms," thereby depriving men of important information pertaining to

their availability when it comes to dating).

♦ Call priests “Father,” followed by their last names (or

just “Father.”). Doctors are called “Doctor.” Professors are called

“Professor.” Use people’s titles.

♦ Don’t interrupt people when they’re talking or busy unless

it’s an emergency or really, truly important. If you must interrupt,

say “Excuse me.”

♦ If you bump into someone, say “Excuse me!”

♦ When someone asks, “How are you?” answer with something

like “Fine, thank you. And how are you?”-- where the "fine" means, at

least, "fine enough for this pleasantry." If it’s a friend or family

member asking, then you can tell him how you really feel.

♦ If you want something, use the words “may I” followed by a

please.

♦ When someone

does something nice for you, say "thank you" and look at the person

you're thanking when you

do it.

♦ Don’t talk on the phone or stare into screens while talking

or eating with others. It’s very rude. Turn phones and screens off and

put them away when you’re with others.

♦ If you make a

phone call, identify yourself to the person

you’ve called. When someone answers, say, “Hi, this is Joseph. I’m

calling for Jane. May I speak to her, please?” If the person goes to

get her,

thank him. If Jane isn’t there, say something like “I’m sorry to have

bothered you. Have a nice day. Bye.”

♦ Don't put people

on speakerphone when others are around without telling them they are on

speakerphone. Phone calls are presumed to be private.

♦ Be a gracious winner: don’t gloat (unless it’s the pretend,

just-for-fun kind of gloating). A “Good game!” or “You played hard”

would go far.

♦ Be a cheerful loser; don’t whine and cry if you lose. “Good

game!” works here, too.

♦ Learn how to introduce people. When you’re with two or more

people who’ve never met, introduce them to each other – the younger to

the elder, the one with less social prominence to the one with more,

men

to women. And let them know something about each other so they’ll have

something to talk about. It might go something like this if your’re

with your friend Lisa, and another friend named Mark walks up, but the

two don’t know each other: "Oh hi, Mark. I’d like you to meet Lisa.

She’s in my class at school. Lisa, this is Mark; he lives next door to

me." Better yet, relate to them something they have in common: "You

both grew up in Virginia."

♦ If you don’t know what to talk about with people, ask them

questions about themselves and really listen to what they say. If all

else fails, there’s always the weather to talk about.

♦ When you talk to people, look at them and give them your

full attention. This includes clerks, waitresses, and others who

perform services for you.

♦ Boys, don’t wear your hats indoors (there are a few

exceptions to this when it comes to special sorts of hats).

♦ Don’t talk about gross things in public (bathroom

stuff, guts, vomit, etc.), and don’t do gross things in public (like

picking your nose or passing gas). Remember the virtue of prudence:

there’s a time and place for everything, and there’s a big difference

between the private life of home, and the public life outside of home.

♦ If you cough, cover your mouth. If you sneeze, use a hankie

to cover your nose and mouth, or sneeze into your sleeve or shirt. If

someone else sneezes, say “God bless you!”

♦ This goes beyond

manners to hygiene -- but involves good manners as well (think about

it): wash your hands after using the restroom, blowing your nose,

touching anything dirty, etc.

♦ Hold doors open for people behind you.

♦ If you put

someone on speakerphone and others are present, let the person on the

other end of the phone know.

♦ If you’re invited to a party, thank the host or hostess

when you leave, and say something nice.

♦ When someone is in your house, make him comfortable. Offer

him a drink and, at least, a snack. Bring him a pillow for his back,

let him take his shoes off, turn on a fan if she's going through

menopause, bring him an ashtray if he's a smoker (unless someone in

your home is allergic or ill), etc. The spirit of hospitality is

illustrated by the Italian tradition of making guests feel less uptight

at meals by purposefully spilling a few drops of wine onto the

tablecloth to lessen any worries they have about making a mess. In that

same light, consider having a wooden box out in your bathroom, clearly

marked "For Guests: Take What You Need" and include in it antacids,

aspirin, things women might need monthly, matches, a few safety pins,

toothpicks, dental floss, a few still-in-their-packaging toothbrushes,

toothpaste, etc. Have the fan on in the bathroom and a radio playing in

it to make bathroom-shy guests feel at ease. Just generally imagine

being your guest, and think of what it would take for him to feel truly

cozy and

unawkward in your home.

♦ If you borrow something, return it as quickly as you can,

and in at least as good a shape as it was when you borrowed it. If it

gets lost or stolen, replace it with at least an equally good

replacement.

♦ Don't make

others' jobs more difficult than they need to be. Return your grocery

carts instead of leaving them for someone else to deal with (or run

into). Have your order ready when the waiter comes. Don't yell at

waiters for bad food (they didn't prepare it) or otherwise blame the

wrong people for something that ticks you off.

♦ When walking with old, sick, or pregnant people, slow down.

♦ Boys, learn how to tip your hat to a lady. It’s very

charming.

When eating:

♦ Make sure your hands are clean at the table.

♦ Don’t blow your nose at the table.

♦ Elbows off the table when the eating begins and until the

eating stops.

♦ Put your napkin on your lap.

♦ Don’t start to eat until everyone’s sitting, everyone’s

been served, and the person with the highest authority begins (at home,

that’s Dad; at parties, it’s the host or hostess).

♦ Eat with your mouth closed, don’t talk with your mouth

full, don’t drink with your mouth full, and don’t make loud chewing,

slurping,

or smacking sounds. Eat quietly.

♦ Don’t gesture with the cutlery. Unless you're Italian and

at home.

♦ Don’t reach over people to get things from the table. Ask

the person closest to what you want to please pass it to you.

♦ Offer to help whoever is cooking, serving, or cleaning up

after meals.

♦ Thank whoever made and served the food. If you enjoyed it,

tell them you did, and what you especially loved. If you didn’t enjoy

it, you can still show gratitude and likely think of something nice to

say – maybe “the food was so beautifully colorful!” or “The table was

set so nicely. I love your centerpiece!”

♦ When you’re done eating and leave the table, push your

chair

back in toward the table.

♦ If you’re eating in a restaurant: Don’t put the waiter in

the position of having to make unnecessary trips back and forth. Figure

out what you want and what you’ll need, and ask for it all at once as

best as you can. Be polite and respectful to those who wait on you; say

“thank you” every time a waiter brings you something. Don’t make

waiters’ jobs more difficult; in fact, make their jobs easier if you

can. If you’re in a fancy place, your cloth napkin goes to the left of

your plate when you leave the table. Don’t forget to tip your waiter

well if you live in a place where waiters rely on tips to survive.

If you want something more comprehensive, there's "Modern Manners: Etiquette for All

Occasions" (pdf) published in 1958. But whatever you read, consider

the importance of manners and hospitality, and teach these things to

your children. Teach them to express gratitude

and to practice what

Aquinas calls "liberality" (generosity, a sharing spirit), two

important parts of etiquette and of Justice itself.

Another aspect of observance is truth-telling (noticing a trend with

these cardinal virtues?). As has been said numerous times in these

pages, do not lie. Honesty is rooted in Justice because we owe others

the truth. We owe it to them to not distort their perceptions of

reality, which is precisely what lying does.

You also owe it to yourself not to lie; it leads to more lies, which

leads to other forms of cover-up, which can lead to greater and greater

evil. You've heard the line from Sir Walter Scott's poem "Marmion": "Oh

what a tangled web we weave when first we practice to deceive." Now

think about it. Say you try to deceive someone about something as

simple as what you were up to one Saturday night. "I was at the movies"

you say. Now the person you lied to asks what movie you saw. You tell

another lie in response. "Who'd you see it with?" "Rick," you answer.

Then you realize Rick's coming over tonight to see you and the person

you're deceiving, so you call him and try to get him to lie as well in

order to cover for you. And on and on it goes. That "one little lie"

led to two more, and to provocation of sin in another person.

Studies have shown the more and more one lies, the less and less

reaction is seen in the amygdala -- a part of the brain that plays a

primary role in emotional response. In other words, that lies lead to

more lies by making lying easier is even reflected in brain imaging.3

Lying also

has a negative effect on health, reflected in "elevated heart rate,

increased blood pressure, vasoconstriction, elevated cortisol, and a

significant depletion of the brain regions needed for appropriate

emotional and physiological regulation." 4 Those who lie

and aren't sociopaths can

feel it in their very bodies; it weakens them. There is shame in it, a

loss of integrity.

Lying can become habitual, and bad habits are exactly what the virtues

are not ("bad habit" is the very definition of "vice"). Don't start the

bad habit of telling lies.

"But what about 'white lies'"? Lies are lies. But dissimulation (cloaking the truth, not distorting

it), evasion, and mental reservation or equivocation (concealing one's

mind or

real intention) can come to the rescue in touchy situations in which

true charity isn't served by the naked truth, others' secrets must be

guarded, and hurt feelings are an issue. Grandma knitted you a hideous

sweater? "Oh, Grandma! You worked so hard on this, and I love it. Thank

you!" could be a response -- where the "it" refers to Grandma's

generous labor of love, not to the sweater itself. "Does this make my

butt look big?" "Baby, I love you no matter what you wear. Come here,

woman, I need a kiss!" or "Hmm, I think that other outfit better shows

off your beauty; you look so gorgeous in that red dress" could work in

response.

About mental reservation, the Catholic Encyclopedia says,

The doctrine was

broached tentatively and with great diffidence by St. Raymund of

Pennafort, the first writer on casuistry. In his "Summa" (1235) St.

Raymund quotes the saying of St. Augustine that a man must not slay his

own soul by lying in order to preserve the life of another, and that it

would be a most perilous doctrine to admit that we may do a less evil

to prevent another doing a greater. And most doctors teach this, he

says, though he allows that others teach that a lie should be told when

a man's life is at stake. Then he adds:

I believe, as at

present advised, that when one is asked by murderers bent on taking the

life of someone hiding in the house whether he is in, no answer should

be given; and if this betrays him, his death will be imputable to the

murderers, not to the other's silence. Or he may use an equivocal

expression, and say 'He is not at home,' or something like that. And

this can be defended by a great number of instances found in the Old

Testament. Or he may say simply that he is not there, and if his

conscience tells him that he ought to say that, then he will not speak

against his conscience, nor will he sin. Nor is St. Augustine really

opposed to any of these methods.

Such expressions as "He is not at home" were called

equivocations, or amphibologies, and when there was good reason for

using them their lawfulness was admitted by all. If the person inquired

for was really at home, but did not wish to see the visitor, the

meaning of the phrase "He is not at home" was restricted by the mind of

the speaker to this sense, "He is not at home for you, or to see

you."...

...All Catholic writers were, and are, agreed that when there

is good reason, such expressions as the above may be made use of, and

that they are not lies. Those who hear them may understand them in a

sense which is not true, but their self-deception may be permitted by

the speaker for a good reason. If there is no good reason to the

contrary, veracity requires all to speak frankly and openly in such a

way as to be understood by those who are addressed. A sin is committed

if mental reservations are used without just cause, or in cases when

the questioner has a right to the naked truth.

In other words, with mental reservations, we know in our minds what is

true, and we speak it to ourselves and to God while allowing a human

listener to jump to conclusions or deceive himself by a wrong understanding.

But this can only be done for just cause or when the person we're

interacting with has no right to the answers he's seeking.

Truth matters. Truth is Christ Himself (John 14:6), and the "Spirit of

Truth" is another Name for the Holy Ghost (John 14:17). Love truth,

seek Truth, and speak truth. In charity!

Epieikeia

Also spelled "epikeia," this Greek word means "reasonableness" or

"equity" and refers to using prudence in honoring the spirit of a law

when following the letter of the law leads to an evil.

When laws are written, they're necessarily universal, meant to govern

in general. But sometimes there are situations in which breaking a law

brings about a greater good than obeying it would. For ex., say the law

says that the speed limit is 45 mph. But it's reasonable that a man

whose wife is bleeding to death would drive 60 mph while trying to get

her to the hospital. Acknowledging that such exceptions exist doesn't

make the law a bad law that doesn't serve the common good in most

cases, most of the time; epieikeia is simply an honoring of the fact

that no lawgiver can foresee every condition to which the law might

apply.

St. Thomas gives this example of epieikeia:

Legislators in

framing laws attend to what commonly happens: although if the law be

applied to certain cases it will frustrate the equality of justice and

be injurious to the common good, which the law has in view. Thus the

law requires deposits to be restored, because in the majority of cases

this is just. Yet it happens sometimes to be injurious—for instance, if

a madman were to put his sword in deposit, and demand its delivery

while in a state of madness, or if a man were to seek the return of his

deposit in order to fight against his country. On these and like cases

it is bad to follow the law, and it is good to set aside the letter of

the law and to follow the dictates of justice and the common good. This

is the object of "epikeia" which we call equity.

You get the point, which can be summed up with "use your head, and

serve the cause of charity above all." Remember this concept if you're

ever in a position to enforce rules.

If you'd like to read more -- a lot more -- about epieikeia, see "The History, Nature, and Use of Epikeia in

Moral Theology," (pdf) by Rev. Lawrence Joseph Riley, S.T.J.

Footnotes

1

There are some parents who are truly abusive, narcissistic,

sociopathic, etc., and sometimes it becomes necessary for a person to

maintain a great distance between himself and those who raised him.

This is an extremely serious, even if sometimes necessary, reality. If

real abuse characterizes your relationship with your parents, talk to a

priest or otherwise seek counsel. Forgive abusers if they repent, and

pray for them always.

2 From "Routledge's Manual of Etiquette,"

late 19th c.

3 Garrett N, Lazzaro SC, Ariely D, Sharot

T. The brain adapts to dishonesty. Nat Neurosci. 2016

Dec;19(12):1727-1732. doi: 10.1038/nn.4426. Epub 2016 Oct 24. PMID:

27775721; PMCID: PMC5238933. URL:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27775721/

4 Leanne ten Brinke, Jooa Julia, Lee Dana

R. Carney. The Physiology of (Dis)Honesty: Does it Impact Health?.

http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/dana_carney/physio.dishonesty.pdf

|

|